Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) offer the capability to prove execution without revealing underlying data, presenting applications in privacy-preserving computation, secure data sharing, and fraud prevention. Learn more about ZKPs in this cornerstone article.

Privacy vs Verification Dilemma

One of the critical features of most decentralized blockchains is their transparency; everything that occurs on these networks is visible to all, ensuring transaction verification and accountability. Yet openness creates privacy concerns. In contrast to banking systems, public blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum fall short of privacy regulations such as the EU GDPR.

Cryptographic techniques have emerged as a beacon of hope in navigating this delicate balance between encryption and auditability. Among these, Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) offer a promising solution to the age-old dilemma of privacy versus transparency. ZKPs enable the validation of statements without revealing sensitive information, thus providing a pathway to both privacy and verifiability.

What Is Zero-Knowledge Proof?

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) are cryptographic methods that allow one party, known as the Prover, to convince another party, known as the Verifier, that a certain statement is true without conveying any additional information. MIT researchers introduced this concept in the 1980s.

Key Properties of ZKPs

ZKPs must satisfy three key properties to solve the privacy vs verification dilemma:

- Completeness: If the Prover is honest and the statement is true, the Verifier will be convinced of the truth of the statement with high probability.

- Soundness: The Prover cannot convince the Verifier of a false statement with high probability.

- Zero-knowledge: The protocol leaks no additional information about the secret beyond the truth of the statement being proven.

Interactive and Non-Interactive ZKPs

There are two broad methods of creating ZKPs based on the degree of communication between the Prover and Verifier: interactive and non-interactive.

Interactive ZKPs

In interactive ZKPs, the Prover and the Verifier actively communicate back and forth in real time. It involves three steps:

- The Prover sends a message (commitment) to the Verifier

- The Verifier returns a message (challenge)

- The Prover then responds to the challenge with a solution (proof)

Interactive ZKP Example

An example might involve proving knowledge of a solution to a complex mathematical problem, such as the 3-coloring problem for a graph. The Prover actively communicates with the Verifier, demonstrating that they can correctly color the graph without revealing the actual coloring. This process involves challenges and responses, where the Prover demonstrates their knowledge while preserving the secrecy of the solution.

Interactive ZKPs Limitations

The interactive proving method is unsuitable in real-life blockchain applications for two main reasons:

- The proofs require more than 1 round of confirmation

- The proofs will be unavailable for independent assessment

Non-Interactive ZKPs

Interactive ZKP is not viable for blockchains. Hence, all ZK protocols use the non-interactive method, as it offers more efficient computation and convenient communication. The Prover generates a single proof independently, without requiring any further interactions with the Verifier. The concept of non-interactive ZKPs was proposed in 1988.

The process is as follows:

- Interaction is monodirectional – the information goes only from Prover to Verifier

- It also involves one crucial element – shared randomness (i.e., common reference string)

Non-interaction is achieved thanks to protocol primitives such as the Fiat–Shamir heuristic. The Verifier is replaced by a hash function that computes over all commitments made by the prover. The hash function's output serves as the challenge, ensuring unpredictability before commitment. Security relies on the hash function behaving as a random oracle, preventing the prover from guessing its output before committing.

Commitment Scheme Example – Pedersen Commitment

In a Pedersen commitment – a cryptographic primitive used in some ZKP schemes – transaction data is substituted by a commitment value, preventing other nodes from manipulating the data. Only the original values used in constructing the Pedersen commitment can satisfy the required mathematical operations.

The process involves two phases: commitment generation, where a plaintext value and a random blinding factor are input to generate a commitment, and commitment disclosure, where the generated commitment is verified to be bound to the claimed value.

Most Popular Zero-Knowledge Proof Systems

SNARKs and STARKs are two branches of zero-knowledge proof technology, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. ZK-SNARKs, introduced in 2012, rely on elliptic curves and offer smaller proof sizes and quicker verification times. However, they require a trusted setup and are vulnerable to quantum computers. ZK-STARKs, introduced in 2018, rely on hash functions and are quantum-resistant. They do not require a trusted setup but have larger proof sizes and higher gas costs.

ZK-SNARKs

zk-SNARKs, or Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge, represent a family of algorithms enabling the demonstration of computation execution without revealing sensitive data. They facilitate confidential computations, scalability, and trustless services by allowing verification of large computations with minimal interaction between parties. Key properties include succinctness, non-interactiveness, and zero-knowledge, ensuring efficient and secure proof processes. The trusted setup ceremony, a crucial step in implementing zk-SNARKs, generates initial parameters to be used in cryptographic operations, safeguarding against false proofs. Overall, zk-SNARKs offer a robust solution for privacy-preserving computations and trustless interactions underpinned by careful management of the setup process.

Take a deep dive into zk-SNARK technology with the MoonMath Manual.

ZK-STARKs

STARKs, or Succinct (Scalable) Transparent ARguments of Knowledge, are cryptographic systems designed to prove computation integrity without revealing sensitive data. They are built on the foundation of the Interactive Oracle Proofs (IOP) model, allowing proofs without cryptographic assumptions. While theoretically ideal, unconditionally secure IOP realizations are deemed unlikely. STARKs address this by transforming Proof-Carrying Proofs (PCP) systems into argument systems.

The Non-interactive STARK (nSTARK) utilizes collision-resistant hash functions to enable interactive proofs, while the latter relies on the random oracle model for non-interactive proofs. STARKs exhibit universality, transparency, and scalability, making them applicable to various computations while ensuring inclusive accountability on blockchains.

STARKs represent a culmination of theoretical advancements bridging theory with practice. They rely on battle-tested hash functions as their cryptographic foundation, ensuring post-quantum security without the need for "cryptographic toxic waste." Recent breakthroughs in quasi-linear PCPs and fast algebraic coding protocols have made STARKs the fastest and most scalable option, surpassing number-theoretic constructions while minimizing cryptographic assumptions.

Learn more in the STARKs research paper.

Bulletproofs

Bulletproofs are a cutting-edge technique for verifiable computation, particularly efficient for range proofs, requiring only 600 bytes. Unlike ZK-SNARKs, they don't rely on trusted setups and work with any elliptic curve with a reasonably large subgroup size, supporting the fastest elliptic curves like Ristretto. Offering linear scalability, Bulletproofs boast optimal performance for proving statements about circuits, with the prover making six group multi-exponentiations of length 2n and the proof size being compact. The verifier's cost scales linearly with the computation size, with benchmarks showing a significantly faster verification time compared to the prover's runtime.

Bulletproofs operate based on a unique format for computation, easily convertible to R1CS and back using linear algebra. The protocol involves agreement between the prover and verifier on the computation, commitment to internal circuit variables, and the proof procedure's execution, leveraging clever inner-product arguments for verification. Implementation-wise, Bulletproofs can use any prime order group where the discrete logarithm problem is hard, with the fastest groups like Ed25519 and the Ristretto group being supported. Bulletproofs are pivotal for enhancing privacy and efficiency in cryptocurrencies like Monero, revolutionizing confidential transactions while enabling a myriad of other cryptographic applications.

Learn more in the Bulletproofs research paper.

Technical Aspects of ZKPs

Elliptic Curves

Elliptic curves, vital in cryptographic contexts, are geometric structures defined over a field, comprising points satisfying specific equations. Their finite, cyclic group nature is particularly interesting, especially in positive characteristic fields, where the Discrete Logarithm Problem is deemed hard if the characteristic is sufficiently large. Pairing-friendly curves, a specialized class, offer advantageous cryptographic properties. In the realm of SNARK development, custom elliptic curves, such as the Baby-jubjub and Tiny-jubjub curves, are designed to facilitate efficient implementation within algebraic circuits for elliptic curve signature schemes in zero-knowledge proofs. Pairing-based systems also necessitate curves with specific security levels and embedding degrees, like the BLS_12 and NMT curves, showcasing the versatility and importance of elliptic curves in ZK constructions.

Finite Fields

Fields are algebraic structures extending the behavior of integers, ensuring that every element (except 0) has a multiplicative inverse. In a field, both addition and multiplication satisfy commutative group properties, with distributivity holding between them. This mirrors the behavior of rational numbers, where fractions extend integers.

Subsets of fields, known as subfields, maintain field properties. Conversely, adding elements to a field while preserving these properties yields an extension field. The characteristic of a field is the smallest positive integer such that the sum of the multiplicative identity with itself equals zero.

In zero-knowledge proofs, fields provide the foundation for cryptographic protocols, facilitating efficient arithmetic operations crucial for computations and ensuring security. Finite fields, especially, simplify cryptographic operations by allowing finite sets of values.

Secure Hash Functions

Hashing in the context of zero-knowledge proofs involves using hash functions to map data of arbitrary size to fixed-size values. A hash function, represented as H, takes input from the set of all binary strings and produces hash values of a specific length, often denoted as k. These hash values are also called digests or hashes.

Cryptographic hash functions, a subset of hash functions, are particularly relevant for zero-knowledge proofs. They possess important properties like preimage-resistance, collision resistance, and diffusion, ensuring that it's computationally infeasible to find a string matching a given hash, to find two different strings with the same hash, and that small changes in input lead to vastly different hash values.

For example, the SHA256 hash function is widely considered cryptographically secure. It maps binary strings of any length to fixed-length 256-bit strings. Utilizing cryptographic hash functions is crucial for the security and effectiveness of zero-knowledge proofs, as they provide a reliable means of transforming data while preserving its integrity and confidentiality.

ZKP Use Cases And Real-World Applications

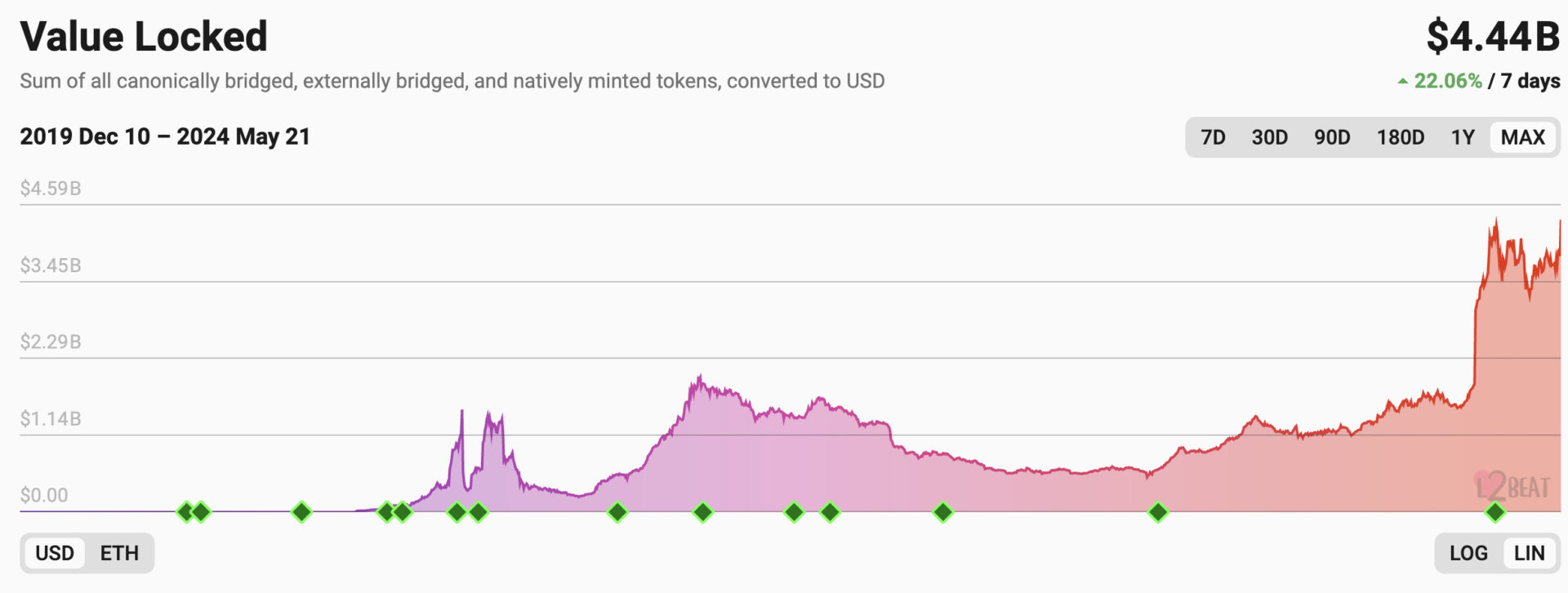

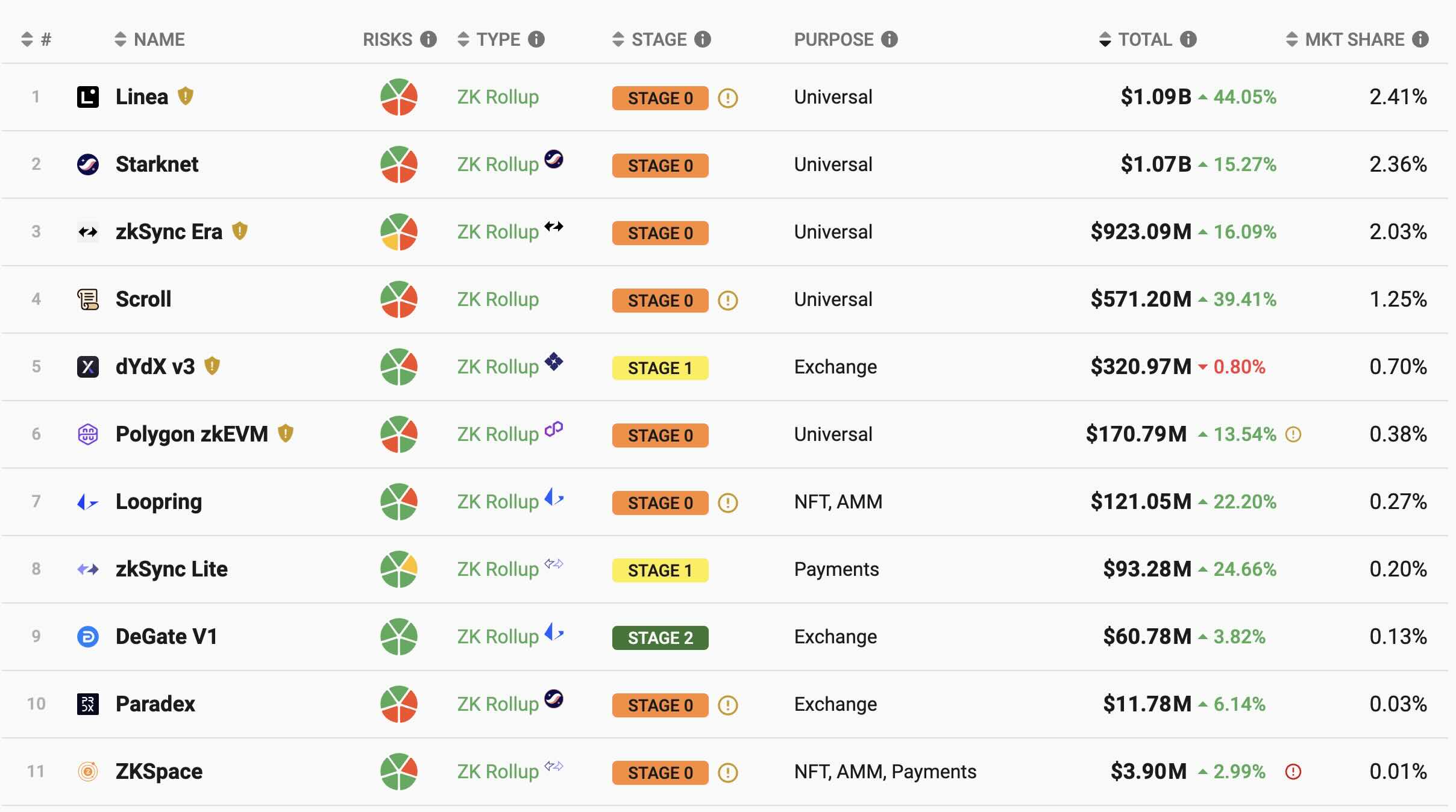

ZKPs have found numerous real-world applications in blockchain technology, including layer-2 rollups that are both scalable and secure. Most rollups still have a long way to go, but they already hold billions in the value locked.

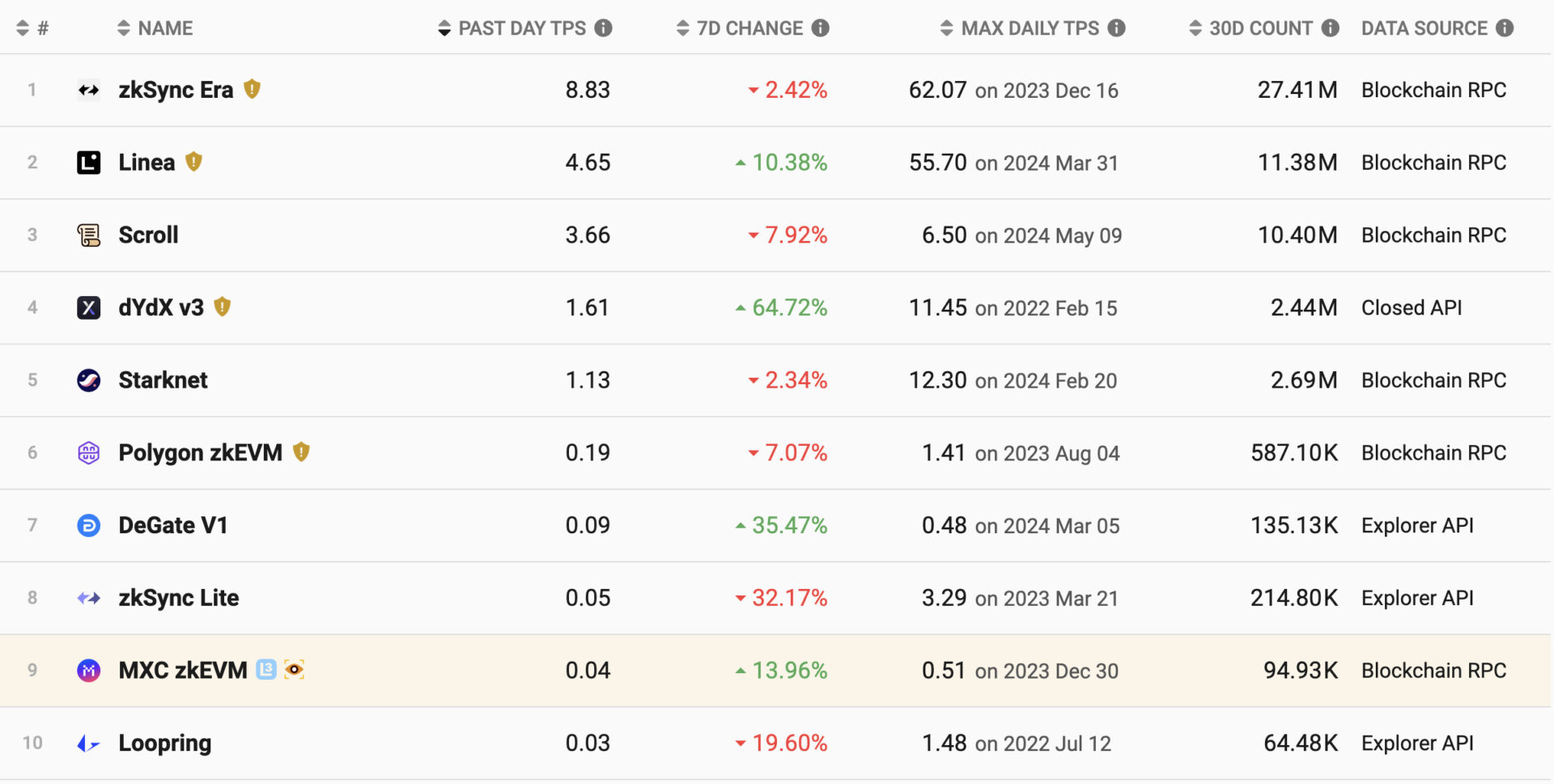

The following data shows the number of transactions on every rollup, giving you an idea of how popular each ZK rollup is.

Starknet

Starknet is a decentralized ZK-Rollup solution built on Ethereum's L2 network, addressing scalability challenges by enabling higher throughput and reduced transaction costs. Starknet employs STARKs for generating proofs of the validity of off-chain transactions. It comprises a Sequencer and a Full Node, both developed in Rust for safety and performance, with transaction execution powered by the Starknet OS in Cairo language. The Starknet Prover, optimized for performance, runs on a cloud-based microservices architecture, while verification occurs on the Ethereum blockchain through a Solidity-based Verifier.

With a total value locked of $1 billion USD, it has attracted over 13,000 active accounts and facilitated over 108 million cumulative transactions. Notably, Starknet achieves a maximum daily TPS rate of 4.16, reflecting its robust scalability and efficiency in processing transactions.

StarkEx

StarkWare, a company developing Starknet, also offers a B2B solution. StarkEx is a permissioned scaling engine tailored for businesses like dYdX and Sorare, ensuring security and scalability with STARK-based validity proofs.

Overview of DeFi protocols built using StarkEx. Image: L2BEAT

zkSync

zkSync is a SNARK-based Layer-2 protocol leveraging zero-knowledge technology to scale Ethereum. With over 230 million transactions since inception, zkSync has deployed over 1 million contracts and allocated over $6 million towards audits and bounties.

Utilizing ZK-Rollups, zkSync employs SNARKs to ensure transaction correctness. This technology allows batches of off-chain transactions to be verified on Ethereum, ensuring their finality through cryptographic validity proofs.

By employing the zkEVM, zkSync remains Ethereum compatible, while offering external validation of transactions, reducing the need for individual node verification. Additionally, zkSync enables the creation of a trustless network of rollups, known as the hyperchain, further enhancing scalability and interoperability.

Zcash

Zcash, at the forefront of privacy-centric digital currencies, embraced zk-SNARKs to encrypt transactions while ensuring verifiability. With the transition to the Halo 2 zero-knowledge proving system during the May 31, 2022 upgrade, Zcash abolished the need for a trusted setup, bolstering performance and scalability. Diverging from Bitcoin's transparent ledger, Zcash prioritizes user privacy, shielding financial histories with full encryption. Zcash stands as a testament to the evolution of digital currencies, offering Bitcoin's conveniences alongside robust privacy features. Zcash boasts a market capitalization of $320.51 million and a trading volume of $6.58 million.

Loopring

Loopring is a rollup protocol leveraging SNARK technology on Ethereum, designed to enhance scalability and security. It processes over 2,000 trades per second while upholding Ethereum's security standards. As a DEX, Loopring offers high-performance trading, similar to centralized exchanges, with users retaining custody of their assets. You can check out how Loopring’s code for ZKP circuits works on GitHub.

Polygon zkEVM

Polygon is one of the most prominent Ethereum layer 2 blockchains utilizing zero-knowledge SNARKs in its architecture. It is a zero-knowledge rollup that scales Ethereum by making transactions faster and cheaper. As the leading ZK scaling solution equivalent to the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), Polygon zkEVM allows seamless deployment of Ethereum Smart Contracts.

Polygon zkEVM focuses on optimizing TPS performance and reducing costs. Key metrics include an average gas fee per transaction of 0.000778 ETH, 516,861 cumulative wallets, 30,103 deployed contracts, $9,647,987 TVL, 131 active wallets, and 367 transactions, with 1,985,484 ZK-Proofs.

Learn more about Polygon zkEVM in our blog post.

Scroll

Scroll is a SNARK-based L2 rollup with a native zkEVM infrastructure. The average block time is 75 seconds, and 38.65 million transactions are processed at 1.18 TPS. The L2 average gas price is $0.000001.

Scroll has undergone multiple public audits by Trail of Bits, OpenZeppelin, Zellic, and KALOS. These audits covered critical code sections across various aspects of the project, including zkEVM circuits, node implementation, and bridge and rollup contracts. This rigorous auditing process ensures the security and reliability of the Scroll protocol.

Mina

Unlike rollups, Mina is a complete L1 blockchain utilizing the ZKPs with smart contracts in TypeScript. It maintains a constant size of 22KB, enabling efficient syncing and verification. Zero-knowledge proofs enable zkApps, offering features like off-chain execution and privacy. The network operates on a PoS consensus called Ouroboros Samisika, requiring minimal computing power.

In Mina, every method internally defines a zk-SNARK circuit. These circuits compile into a single prover and verification key. The proof verifies that a method was run with private input, producing specific account updates. The account updates serve as public input, and the proof is accepted only if it verifies against the stored verification key, ensuring adherence to smart contract rules. With almost 900M in mcap, Mina is a promising alternative to ZK rollups.

Implementing Zero-Knowledge Proofs

Below are various sources and frameworks for learning about ZKPs and their implementation. Moreover, current ZK protocols provide plenty of developer resources.

Languages & Libraries

- Circom: Circom allows users to design custom circuits with specific constraints, and the compiler generates the R1CS representation necessary for ZKPs. ZKPs enable demonstrating the satisfiability of circuits, proving possession of signals that fulfill the circuit's requirements, known as the witness.

- Halo2: Halo2 is a zk-SNARK language incorporating various concepts such as proof systems, PLONKish arithmetization, chips, and gadgets, enabling the creation of efficient and transparent zero-knowledge proofs.

- Noir: Noir is a Domain-Specific Language (DSL) for SNARK proving systems developed by Aztec Labs, offering a simple and flexible syntax for generating complex ZKP without prior knowledge of underlying mathematics or cryptography.

- Snarkjs: Snarkjs is a versatile JavaScript and Web Assembly library implementing zkSNARK and PLONK schemes, facilitating trusted setup multi-party ceremonies and providing compatibility with Semaphore's Perpetual Powers of Tau, allowing seamless integration into projects for high-performance zk-snark operations.

Guide to Creating a Basic ZKP Circuit

Implementation Steps:

- Setup Dependencies: Before working with ZKP circuits, set up necessary dependencies including Rust for building Circom from source and installing Snarkjs.

- Create and Compile the Circuit: Define the ZKP circuit by creating a circuit description file, often with a .circom extension, and compile it using Circom.

- Generate the Witness: Generate a witness, a set of inputs, intermediate values, and outputs captured by running the computation defined in the circuit.

- Generate the Proof: Create a proof of correctness for the computation using the witness and a trusted setup, with tools like Snarkjs.

- Verify the Proof: Verify the proof's correctness using the verification key, ensuring its validity based on the provided public inputs.

- (Optional) Verify Proof via a Smart Contract: Optionally, deploy a verifier contract on a blockchain network to verify proofs on-chain using Snarkjs-generated Solidity smart contracts.

This guide by Jordi Baylina provides an overview of the implementation steps involved in working with ZKP circuits using frameworks like Circom and Snarkjs.

Useful Learning & Coding Resources

- A list of resources for learning ZKP, by Matter Labs (free)

- ZK whiteboard video tutorial, by zeroknowlage.fm (free)

- Learning Circom and Halo2 programming languages, by 0xPARC (free)

- Coding ZKPs for beginners, by Santiago Palladino (free)

- ZK bootcamp, by Rareskills (paid)

Zero-Knowledge Security

Programming ZK implementation is more knowledge-intensive compared to traditional smart contract building. ZK programmability introduces complex security challenges, including logic bugs. ZK programs feature private inputs and non-deterministic computations, requiring careful handling to prevent data leaks and ensure security. Proof systems, a crucial component of ZK, require meticulous implementation due to underspecified protocols and potential vulnerabilities, exemplified by past incidents like the Zcash Counterfeiting Vulnerability. Trusted setups, often necessary for certain proof systems, involve collaborative ceremonies to generate critical values, albeit posing logistical challenges and security risks if mishandled.

Complex Vulnerabilities in ZKPs

- Under-Constrained and Non-Deterministic Circuits: Lack of constraints allows for fake proofs and violates determinism, risking double-spending.

- Arithmetic Over/Under Flows: Operations over prime finite fields can lead to unexpected behavior like double spending.

- Mismatching Bit Lengths: Different bit lengths allow manipulation of inputs, compromising system integrity.

- Unused Public Inputs Optimized Out: Unutilized inputs can cause critical errors in protocols due to optimization.

- Frozen Heart: Fiat-Shamir implementation flaws may forge zero-knowledge proofs.

- Trusted Setup Leak: Inadequate disposal of toxic waste during setup enables forging of fake proofs.

- Assigned but Not Constrained: Misunderstanding between declarations and constraints may lead to security breaches.

To address these risks, developers can employ solutions such as language improvements, VM enhancements, safer libraries, audits, and formal analysis. It’s important to understand that even the biggest developer teams can make mistakes. Hacken discovered a critical bug in Binance's ZK-Proof-of-Reserve. Therefore, we recommend thorough security audits for any zero-knowledge implementation.

Conclusions

Zero-knowledge proof generation and validation revolutionize privacy in decentralized systems by allowing verification without revealing sensitive data. This technology serves as a bridge between privacy and transparency. ZKP systems like zk-SNARKs, zk-STARKs, and Bulletproofs offer different trade-offs in proof size, complexity, and security.

Implementing ZKPs demands expertise in cryptographic concepts like elliptic curves and secure hash functions. Despite their promise, ZKPs are prone to common and very complex vulnerabilities, emphasizing the need for rigorous security measures.